B. Berkeliev

No one speaks truth or wisdom anymore,

No one distinguishes lies from the law,

No one can tell what’s dirty from what’s clean,

The line ‘twixt fair and foul we now ignore.

– Magtymguly Pyragy

Considering the volume of military resources deployed, the quantity of countries involved (over 50, the Ramstein group), and the unprecedented economic sanctions imposed by the West on Russia, it is hard to disagree with the opinions of experts who claim that the war in Ukraine is not a local war but is rather the beginning of the Third World War. The fact that NATO’s large-scale military assistance and immense sanctional pressure has not been able to break Russia’s economy and military capacity, has created a challenge not only for the economic well-being of the West, bringing down the quality of people’s lives, but it has also become the biggest test of America’s monetary system and financial control of the world. This war has boosted the military-industrial complexes of numerous countries, having forced their governments to reallocate massive resources from the budget to the detriment of the country’s social programs. In 2014, three NATO allies spent 2% of GDP or more on defence; the list of allies increased to seven by 2022. The growth of military capacity has become if not a priority, then in all cases at least a trendy policy for the modern Western politicians.

In addition to the military might of a state, which, according to the existing and established political tradition in the world, allows for the seizing and the exploitation of foreign markets – the total political and economic potential of a country also has an internal metric, which is the measure of social well-being: mainly determined by the principle of fair distribution of wealth. In his extensive study of the economies of the now developed countries over the past 300 years, economist Thomas Piketty came to the conclusion that the unfair distribution of state wealth leads to its concentration, which ultimately leads to economic instability, which in turn leads to social tension. Piketty explains this by comparing the level of return on capital (r) with the level of economic growth (g). His thesis can be summed up as that if r is higher than g, then in the long run this inevitably leads to the concentration of capital, and this violates the principle of fair distribution, which in turn causes an economic crisis and social tension.

To illustrate this more extensively: the growing economy, first of all, is the creation of added value. If I buy 4 kg of boards for $5 and make one stool out of them and sell it for $7, then I have created an added value of $2. There will also be lumberjacks who will have made a profit from this operation, board makers at the sawmill, nail or glue makers as well, tool makers that I used while making my stool, and even a garbage collector, the supplier of my electricity, water and heating. But when one broker purchases shares or cheap loans from another and sells them at a higher price, they enrich themself yet do not create added value. I will be dependent on the prices of the products that I use to make my stools, but the broker is comfortable: they can always sell expensive money. My earned two dollars are not enough to feed my family and buy a new supply of boards and nails for future use for several months, so I will need loans. But if the economic situation of the entire population is deteriorating due to expensive loans, then people will not particularly want to buy my stools, the price of which will have increased significantly due to the need to pay interest on my loan. Then a merchant will appear who can import cheap and unethically made stools from a foreign land and my production will become simply unprofitable, and I will become bankrupt.

In such an economic model, a massive proportion of producers and manufacturers go bankrupt and the layer of the middle class in the society thins out. And in fact, the middle class, with its economic independence and education, is the class that can still control its government so that it does not go completely out of line.

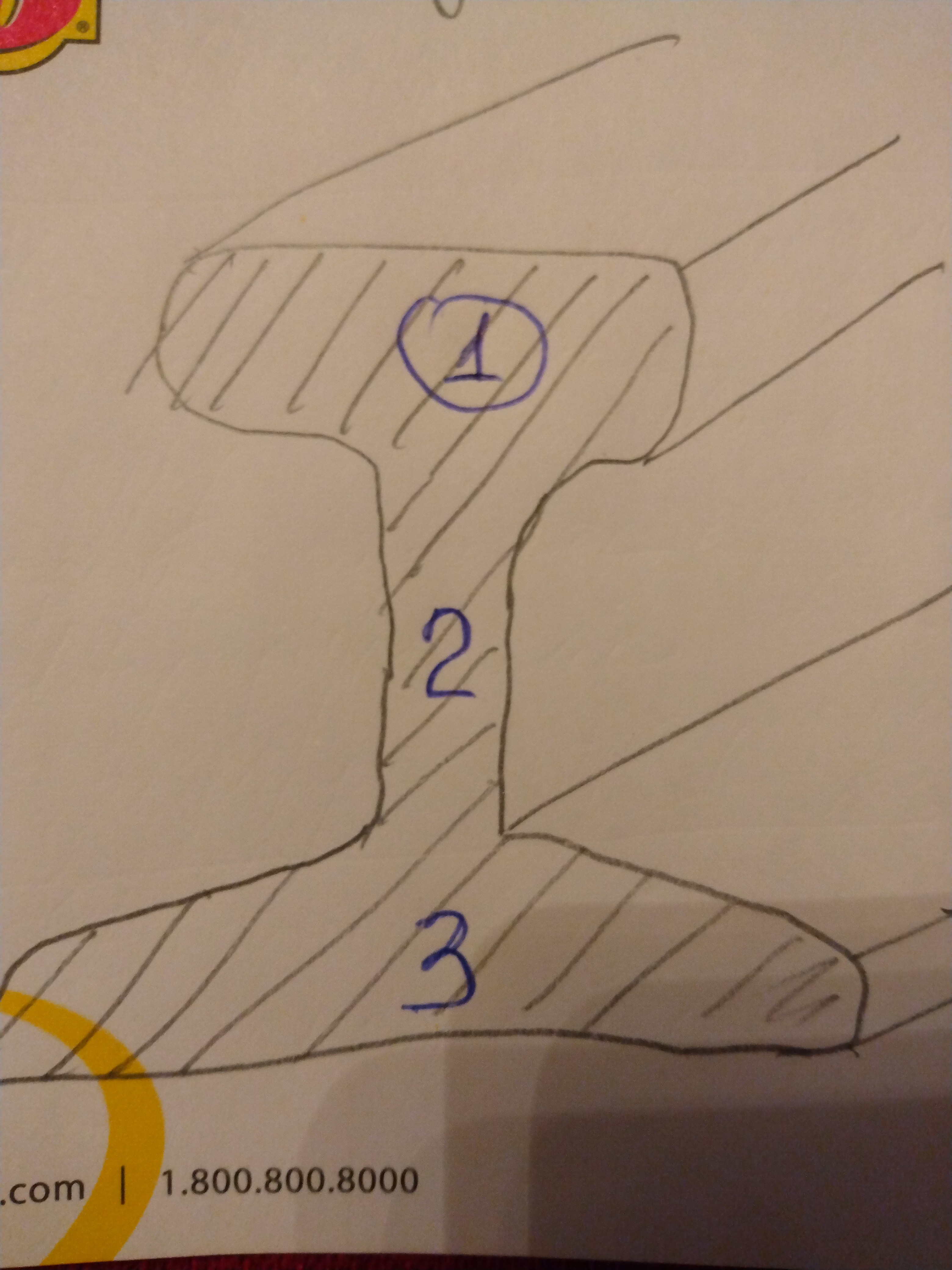

To explain this situation another scholar named Emanuel Todd used the cross section of a railroad rail (see attachment). The upper part (#1) is the financial and managing elite, the middle part (#2) is the middle class, and the lower part is the impoverished marginalized strata of the population. When the middle layer thins out, the precariat layer grows and the lower part of the rail increases greatly, and then as a rule to the power can come to any showman adept at manipulating people, who in the end turns into an odious dictator.

Of course, there are many statistical parameters, such as child mortality and suicide rates etc., which can be telling of the economic and mental health of the society. Let’s look at three of them.

As of June 2023, nearly 250,000 Canadian small businesses are at risk of closure due to the country’s economic instability and rising interest rates. That is 19% of all small businesses, or roughly 1.6 million Canadians at threat of losing their job by 2024. 2,861 Canadians died from opioids in 2016, averaging out to nearly 8 lives lost per day. These numbers have risen by over 150% to 2022 when 7,328 Canadians died from opioids, averaging out to 20 lives per day. Following a similar trend, between 1961 and 2009, a span of nearly 50 years, 133 police officers were murdered in the line of duty, averaging to less than 3 per year but in a six-month span between the fall of 2022 and the spring of 2023, 8 police officers were murdered.

This data suggests that Canada’s economic and social situations have become increasingly similar to those situations described by Piketty and Todd. This must cause concern and cast doubt on the correctness of the direction of Canada’s current governing party.